MokshaTrek is a modern reimagining of Mokshapatam, the 13th-century Indian board game created by Sant Dnyaneshwar, which inspired Snakes and Ladders. Unlike the modern version, the original game symbolized life’s journey — ladders for virtues and snakes for vices — teaching reflection and values.

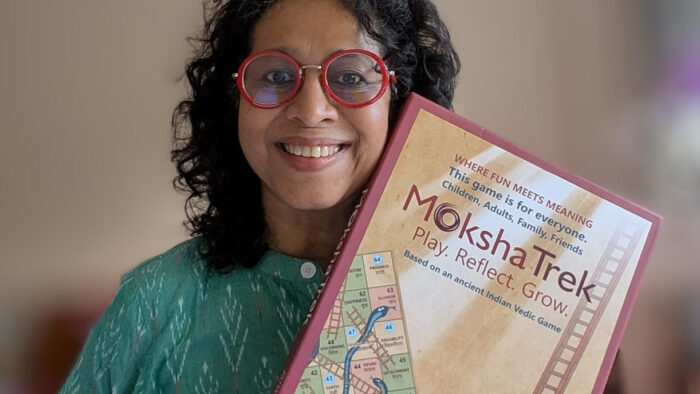

Designed by communication and graphic designer Falguni Gokhale, who first researched it years ago, MokshaTrek blends traditional wisdom with contemporary design. It invites all ages to play, reflect, and converse through beautifully illustrated boards, prompts, and a QR-linked website explaining key concepts.

The creator emphasizes that Indic games carry the soul of Indian culture, encouraging learning, connection, and mindfulness over competition. MokshaTrek’s tagline - “Play. Reflect. Grow.” - captures its aim to revive ancient wisdom in a modern, joyful form.

What was it about Mokshapatam that first caught your imagination and made you want to reimagine it for today’s world?

I have always been fascinated by how our ancestors encoded wisdom into simple, everyday forms, whether in song, craft, or play. When I first came across Mokshapatam, while researching for a personal art project, I realised it was not merely a game, but a complete philosophy of life mapped on a board. The idea that one could journey from ignorance to awareness through play felt timeless and universal. I wanted to bring that experience back, not as nostalgia, but as something relevant to our times where reflection and conversation have almost disappeared.

How did your research into the original game influence the design choices in MokshaTrek?

I tried to interpret the layers in the game visually, through symbols, colours, and materials, so that the board itself feels contemplative and not merely decorative. Also I put a layer of conversation, reflecting and action as rules and prompts to hopefully make it more interesting.

Sant Dnyaneshwar’s version carried deep moral symbolism. How did you interpret or adapt that for a modern audience?

Sant Dnyaneshwar’s simplified the Geeta and that every action arises from a state of mind. I retained that essence but reworded some of the virtues and vices. I wanted children and adults alike to understand the emotional and ethical weight of these words without needing translation. The idea was not to moralise but to prompt reflection.

When you first encountered Mokshapatam, did you see it more as an art project, a teaching tool, or a spiritual metaphor?

It began as an art project, then morphed into a game design project, which also has became a teaching embedded into it. Somewhere along the way, it stopped being a project and became a personal exploration.

Designing the game was like meditating with colours, forms, and meaning; it was a dialogue between play and purpose.

You mentioned your background in communication and graphic design. How did that shape the look and feel of the board?

As a communication designer, I am constantly balancing clarity with emotion. I wanted MokshaTrek to look inviting, not preachy or old fashioned. The visual language had to carry depth, yet remain accessible. The colours, the typography, the textures, everything was designed to evoke stillness and curiosity. Even the snakes and ladders were reinterpreted as forces of the mind, beautiful yet unpredictable.

How did you decide which virtues and vices to include on the MokshaTrek board?

I went back to the Dnyaneshwari and relooked at the words and which I felt were more relevant in our modern life. But I also added neutral spaces for reflection because life is also about awareness in the in between.

Can you describe one or two design elements that carry a deeper symbolic meaning?

The blue lotus squares mark are where the player pauses and reflects before moving on. Even the QR code on the board acts as a bridge between ancient and modern, leading players to meanings and reflections online.

What were some of the biggest challenges in balancing aesthetics, authenticity, and playability?

That was the hardest part. I wanted the game to retain its Indic essence but not feel museum like. It had to be playable by children and meaningful for adults. The challenge was simplifying without diluting, while ensuring it remained a joyful experience. Every design decision, from the board layout to the word choice, went through that test.

You said “games are never just games.” What values or ways of thinking from Indian civilisation do you think modern gaming has lost?

Modern gaming often focuses on competition, speed, and winning. Our traditional games celebrated rhythm, balance, and inner growth. They were microcosms of life, teaching resilience, ethics, and the art of letting go. I think we have lost that sense of play as practice, where fun and wisdom coexist.

How can reviving Indic games like MokshaTrek reshape how families and schools think about learning?

I think they can restore conversation. When families play MokshaTrek, they laugh, tease, and also talk about choices, about values, about life. Schools can use such games to teach not just morals but emotional intelligence. Learning through play creates memory; it stays longer because it is felt, not forced.

Do you see potential for similar reimagining of other traditional Indian games?

Absolutely. Our country is a treasure trove.

What does MokshaTrek tell us about how our ancestors viewed life, ethics, and growth?

It tells us that they saw life as a journey of consciousness, not just circumstance. That joy and sorrow were both teachers. That virtues were ladders not to heaven, but to awareness. And that the ultimate game is not against others; it is within oneself.